LifeScanner is an iOS app and kit that uses DNA barcoding technology to help people discover the diversity of living organisms around them. By providing access to scientific data in an easy-to-use platform, LifeScanner allows non-scientists to explore species, educate themselves, and make informed decisions while contributing to a global biodiversity knowledge-base. In this interview, LifeScanner Founder and CEO Sujeevan Ratnasingham shares his story, mission, and vision for the future of biodiversity.

Let’s begin with some background about who you are and what you do.

I’m currently the Associate Director of informatics at the Center for biodiversity genomics, and Adjunct Professor at the University of Guelph. Apart from that, I am the founder and CEO of LifeScanner.

I was a computer scientist and got into biology around the year 2000, when I met my friend and mentor Paul Hebert. He was a faculty member at the University of Guelph, and he introduced me to DNA sequencing and molecular biology. That got me really excited about the potential to use computer science tools in order to improve our understanding and connection with biology and biodiversity.

Since that point, I’ve been working with him on a global project called DNA Barcoding. It is the process of using short pieces of genome to identify species and give them a name, even when you don’t know anything else about them. The moment you have a name, you can gain a much better understanding of how that species interacts with other organisms in the environment.

When multiplied on a global scale, this simple concept makes it possible to model ecosystems at finer detail because you have accurate information on the organisms living in an ecosystem.

Over the last 20 years, this concept has expanded into a global project we call BioScan, with the goal of documenting the movement and interactions of organisms, using their DNA.

While going along this journey, I recognized that even though the technology was amazing, it was still relegated to the academic space and was not being utilized to a commercial degree. So in 2013, I partnered with SAP, a large multinational software company in Ontario, to try and bridge that gap between science and industry, and that’s how LifeScanner was born.

Using LifeScanner, individuals with no experience can go out to the field, collect samples into a vial, scan them with our mobile app and ship them over for us to analyze. The results would then flow back to their mobile device in the form of an alert, and they would know exactly what species it was.

In 2015 it became clear that there was a lot of interest in this kind of service. In 2017 I spun out the company and that made it available to many different people. Nowadays, LifeScanner is used in the industry quite a bit, especially in food validation and forensic applications.

Here’s a quick introduction to what LifeScanner is all about:

What are some interesting use cases for LifeScanner?

One very common use case is around food, especially seafood. We’re working with NGOs like the David Suzuki Foundation and SeaChoice, who use LifeScanner kits to conduct seafood surveys across Canada. They’ve done that multiple times and found lots of cases of fraudulent and mislabeled products. That data has been submitted to regulatory agencies to address and deal with. At the same time, businesses have used our kits to test grocery products themselves and build a trusting relationship with their customers.

One interesting case was when the city of San Diego purchased 1000 kits and put them in 30 public libraries, just like books. Students would borrow them and then go out and document life within the city. It was a very exciting project, part of a smart city project with sociological components, but ours was the biodiversity component. We actually found new species in San Diego while doing that. So while helping kids and parents engage with nature, we’re also contributing to the scientific effort.

On the other end of the spectrum, we’re working with law enforcement agencies like the South African Police Services and their Department of Environmental Affairs on mitigating wildlife crimes where criminals are poaching the movement of endangered species as pets or as traditional medicines. Often, the criminals involved would obfuscate the evidence, so visual inspection gets harder and harder. But the beauty of DNA testing is that it is very hard and expensive to synthesize. So right now, LifeScanner is being used in a regulatory context.

We have a case that is currently in the court, where law enforcement officers had used LifeScanner kits to test material and found that it was in fact a case of poaching, which led to prosecution.

Another common application is bird strikes. When a bird flies into a plane engine, causing it to crash or disfunction, the hurt bird gets sent to us. We tell the aviation industry what bird it was so they can take the necessary precautions, based on migratory patterns.

On average, it takes about 5-8 days to get an answer from LifeScanner kits. That’s great if you have a pest in your backyard because you don’t want to just spray everything. I once had a tiny caterpillar eating lots of holes in one of my cherry trees. It was undoubtedly going to spread. I could have just sprayed the tree to high heaven until every insect on it was dead. But instead, I put it in a LifeScanner vial and sent it to the lab. It turned out to actually be fly larvae, and part of its life cycle was to drop into the soil, so it was easier to treat it in the soil than on the tree. That’s the traditional way to deal with pests: find a way to disrupt the life cycle instead of just killing it where it’s doing the damage, and prevent it from getting there in the first place.

I can see this being used by farms, where a 5-8 days turnaround is acceptable. But when it comes to law enforcement, you can’t detain people or have them sit in the airport while you wait 8 days to determine if they’ve broken the law. So we’ve taken a step further and created a lab in a box, which provides portable and low-cost access to individuals that otherwise wouldn’t have access to a lab. When packed, it fits into roughly one cubic foot. When deployed, it would just take up a standard office. Using that, you would be able to analyze a LifeScanner vial and get results within six hours.

We recently had one of these boxes deployed at the Department of Environmental Affairs in South Africa. I was there in February to run a workshop on its use. We set up the lab to analyze the samples and confirmed that they were accurate. Obviously, it was an opportunity to do a pilot. We’re not law enforcement agents, so our results were just confirmatory, but it was really rewarding to be on-site and do that work. Currently, we’re just continuing to expand and improve so we can provide lab access to as many people as possible.

How do you utilize the data that you collect from your app, and what are you hoping to achieve?

Biodiversity data that people collect and identify has two main uses. One is to contribute to our knowledge base, which is freely available to the scientific community. The DNA, combined with the location where that species was found, are both really important factors.

In my backyard, I find a lot of species that should not be there because I’m in an urbanized environment. But occasionally I also find species that definitely should not be there, like emerald ash borer or some new pest. If it’s very rare in the region, but really abundant overseas, then it’s likely to be an invasive species. We had one case of this that’s been covered in the media, where someone ordered a bag of roasted pistachios from California and found a little cooked worm in it. They sent it to us and it turned out to be a particular moth that had no known relationship with pistachios. So that individual wrote the producer, saying they have a pest. The company replied that it was a pirate worm, but that wasn’t the case. It was a different species that was abundant in Costa Rica, and definitely not in California. Climate change is driving this species further and further north.

We informed them that they had a new pest, and they could do what they will with that data. But when we find a new pest, what we like to do is report to the forestry agencies. Anything that can be managed needs to be reported. Canada’s lost billions due to invasive pests like emerald ash, which continues to ravage ash trees even now. Knowing when it gets to a new location is very useful.

When it comes to things like biting insects, a lot of people use our service to know what bit them. In some of those cases, we don’t share the data because it’s personal. We have categories where we make the data publicly available and others where we don’t.

When it comes to food testing, we’ve partnered with the Captain Planet Foundation and Let’s Talk Science, two educational NGOs that provide our kits to school kids to expose them to DNA analysis and actually play with DNA sequences.

When it comes to food surveys, we obfuscate the restaurant or the grocery store’s name. We certainly don’t want to create an environment of “gotcha journalism”, although journalists have used our tool to criticize restaurants and put them on the spot. At the end of the day, I do feel it’s important to empower people to have access to data so they can fix the problems themselves, and that is what we truly aim for.

I’m really hoping that grocery stores will start to validate their supply chain using our tools. We recently partnered with a seafood provider who is testing products prior to import, so they can find problems before the produce even reaches Canada.

I believe this tool has an educational role for individuals. I take my daughter around for walks in the woods close to our home. Often, she’ll ask me what something is and I wouldn’t know. I’d Google the heck out of it and I still can’t find what it is. At that point, I’ll throw it into a LifeScanner vial and send it off, so I can answer the question. By doing that, I show my daughter that knowledge is something to be pursued, and that is something I’m truly passionate about.

How can LifeScanner reveal food fraud?

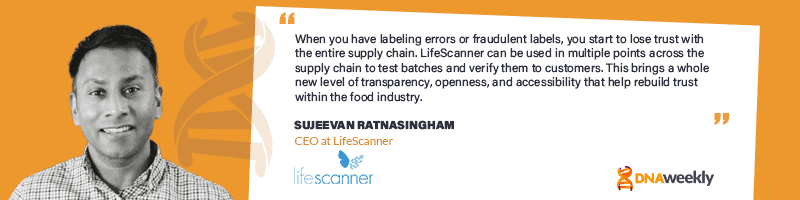

It can help in two ways. In terms of food fraud or accurate labeling, the real problem is trust. When you have labeling errors or fraudulent labels, you start to lose trust with the entire supply chain, little by little. I wouldn’t say trust is gone completely, but if the problem continues then trust is going to be diminishing over time.

The supply chain is long. It’s not fair to just blame the retailer. Even though the consumer buys from the retailer, the responsibility lies throughout the entire supply chain. The great thing about LifeScanner is it can be used in multiple points across the supply chain. When a retailer buys from a wholesaler, they can test the batch and confirm the test to their customers. The customers have the option of confirming the test on their end and getting a whole new level of transparency.

When the customer can use the exact same kit to test the product on their end, that’s the strongest certification you can have. That kind of openness and accessibility rebuilds trust. I don’t think it has to happen for very long or very frequently, but once supply chains start to adopt it, all problems will be mitigated much more efficiently.

Obviously, every marketplace has the potential for fraud and shortcuts, so there has to be a minimum level of testing. Regulation has been slow, underfunded, under-resourced, and understaffed, so we have to push back on the commercial side of things. I believe LifeScanner has a role in helping the private sector provide this level of trust and transparency. That’s my goal, that’s my mission. We’ll see how well it pans out.

Which trends or technologies do you find to be particularly interesting these days?

I think the most interesting trend is the miniaturization of genomic technologies. We’re seeing some of this happening with COVID-19 testing, where a crisis created an opportunity for innovation. Lab devices and their different components are being miniaturized. It’s this miniaturization that allowed us to take a lab and put it in a cubic foot of equipment.

There is going to be a point where labs will get down to handheld size, and the cost would get significantly lower. You’d be able to do genetic analysis on the spot, in a short timeframe.

I grew up with Star Trek, like many people my generation have. The concept of the tricorder, even though it’s dated, has been maintained throughout the different iterations of the Star Trek genre, because of the recognition of barriers to information and the benefit of immediate access to information.

This is what Google did. That’s why Google is a verb, that essentially means, aside from using Google, asking a question, and getting an immediate answer. I think that’s going to be incredibly transformative, equal in grandeur to when GPS was added to our mobile phones.

We live in a bio-diverse world that we’re not interacting with, because of a lack of knowledge and lack of access. COVID is a case of not interacting with the biodiverse world effectively. It’s a virus that’s jumping from one species to another. Recognizing those actions and understanding how they could lead to problems would have been easier if it wasn’t for the lack of information. I can’t predict how those tools are going to be used in the future, but I know they are going to change the world.